| Resurrection Home | Previous issue | Next issue | View Original Cover | PDF Version |

Computer

RESURRECTION

The Bulletin of the Computer Conservation Society

ISSN 0958-7403

Number 39 |

New Year 2007 |

| Top | Previous | Next |

Welcome to the first 2007 issue of Resurrection. This is a very significant year for our parent body, the British Computer Society, which will be celebrating its Golden Jubilee. Computing as a profession will shortly be 50 years old! The CCS has been heavily involved in the planning of various activities to celebrate the occasion.

The focal point of the Jubilee will be a three day conference in July, with the first day being held at Bletchley Park and the last two days at the BCS headquarters in London. The Bletchley Park segment will focus on the challenges involved in reconstructing pioneer machines, a topic where the CCS can claim to be the most expert body in the world! The London part of the event will take the form of a conference on the history of computing and the part played by the BCS in that history. Readers who wish to go to only one of these events can book for it separately. Ticket prices had not been finalised as we went to press, but are likely to be of the order of £25 for each segment.

The North-West Group of the CCS is involved with the Manchester branch of the BCS in organising a separate event for the north of England.

The CCS has also collaborated with the BCS in producing a glossy brochure commemorating the first 50 years of the BCS. It will be given to each attendee at the London part of the jubilee conference.

A second major event for the CCS in 2007 will be the formal switching-on of the rebuilt Bombe, also at Bletchley Park. To avoid overcrowding, this will take place on a different day from the Jubilee conference.

This year will also mark the 50th anniversary of Fortran. Picking the precise moment for the genesis of a programming language is difficult, as there is a gap of several years between first conception and general availability. The start point for Fortran is now generally recognised as 1957, on the grounds that that was when the first commercially available compiler was released.

The CCS has teamed up with the Fortran Specialist Group of the BCS to run a celebratory conference later this month (January). Details can be found within on pages 4 and 31.

| Top | Previous | Next |

-101010101-

Members have generously responded to our call for an increase in voluntary subscriptions in the last issue, and £2200 had been banked by November. Any reader who has been meaning to subscribe and has forgotten can still send a cheque for £15 to our Treasurer, Dan Hayton.

-101010101-

The BCS 50th anniversary conference will take place from Thursday 12 July to Saturday 14 July 2007. The first day's proceedings will be held at Bletchley Park, with the next two days taking place at the BCS offices in London.

-101010101-

The North West Group of the CCS is teaming up with the Manchester branch of the BCS to put on their own event celebrating the jubilee, a "Faraday lecture" style event on the history of computing.

-101010101-

Pete Chilvers has joined the Committee as representative of the volunteers working at Bletchley Park, who are now known collectively as the Support Organisation of the National Museum of Computing. Pete replaces Michelle Moore.

-101010101-

The Committee is considering making Resurrection available by email instead of (not as well as) post to those members that wish it. Would any reader who would prefer to be on an electronic rather than the postal circulation list please contact the Editor (by email!).

-101010101-

The Committee is looking for a volunteer to coordinate relationships between the CCS and other similar bodies overseas. Anyone interested should contact the Chairman or the Secretary.

-101010101-

Readers intending to visit Bletchley Park during the winter may like to note that it closes at the earlier time of 1600 (compared to 1700 in summer). Opening times are the same: 0930 on weekdays and 1030 at weekends.

-101010101-

The CCS has joined forces with the BCS Fortran Specialist Group to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the release of the first Fortran compiler by IBM in early 1957 with a one day meeting at the BCS Headquarters on 25 January. Readers who would like to go should check the Web site at href=http://www.fortran.bcs.org/2007/jubileeprog.php>www.fortran.bcs.org/2007/jubileeprog.php for full details.

-101010101-

All officers and members of the Committee were unanimously re-elected to serve for another year at the Society's AGM on 4 May.

-101010101-

The principal news item announced at the AGM was that the reconstruction of the Bletchley Park Bombe is now complete. This major milestone has been reached after nearly nine years dedicated work by John Harper and his team. John estimates that another year or so will be needed to complete the commissioning. His latest report can be found on pages 7-9. The team's achievement was reported in The Times on 7 September 2006 and achieved widespread coverage elsewhere.

-101010101-

| Top | Previous | Next |

It seems about time to remind members, and to inform recently joined members, that for the past six years the IEEE has allowed members of the Computer Conservation Society to subscribe to their authoritative publication at a concessionary rate. (Strictly the concession is supposed to be limited to members resident in the UK.) The present subscription for CCS members is £30. Some 40 members currently subscribe, and they have recently received a renewal application with Number 4 of the 2006 Volume which was distributed in December. Other members are cordially invited to join the scheme.

Volume 27 Number 3 was devoted to Historic Reconstructions, and contained articles on Thomas Fowler's Ternary Calculating Machine, Konrad Zuse's Z3, the Manchester Baby, the Rebuilding of Colossus, the Construction of Babbage's Difference Engine, and even something about an IBM 1620. A very few copies are still available, and you don't have to be a subscribing member to get one. First come, first served.

Contact Hamish Carmichael at hamishc@globalnet.co.uk.

| Top | Previous | Next |

Kevin Murrell, Chairman

Digital's headquarters in the UK since the 1960s has finally closed its doors. Of course it is now Hewlett-Packard that is turning off the lights at Worton Grange. We have been able to collect the remains of the Decus documentation that remained there.

After Christmas the group is to collect an early PDP-8 from Edinburgh - a 1965 model that is fully expanded to include three DecTape drives.

The group is in touch with many ex-Digital engineers, but is always pleased to hear from others with practical experience.

Contact Kevin Murrell at kevin@ps8.co.uk.

Simon Lavington, Chairman

1. In July a group of volunteers agreed to compile technical information on English Electric computers for the Pilot Study website. Because there already exist substantial (Australian) Web sites for Deuce, the group's initial emphasis will be on the KDF and KDN ranges of computers. Anyone possessing EE documents is asked to contact one of the following:

Brian Wichmann: brian.wichmann@totalise.co.uk

Peter Stanley: phstanley@tiscali.co.uk

Robert Beard: bobbeard@hotmail.co.uk

2. In April the CCS agreed to collaborate with the BCS on five items, to mark the Society's 50th anniversary. The first item was "to collaborate with John Kavanagh on producing a (32-page or similar) glossy brochure on the BCS' first 50 years". The last was "to develop a Web site using material compiled for 'Our Computer Heritage' project".

This last item was amplified: "The intention would be to use volunteer effort to make the material being collected by CCS volunteers available in as attractive a form as possible but without paying professional Web designers. BCS would be asked to host the pages on the Web site. Some incidental costs could be incurred which the CCS may be able to meet or may need limited additional help".

On 16 June Roger Johnson and Simon Lavington met with Brian Runciman (BCS Managing Editor) to draw up the requirements for the historical Web site, which was envisaged by Brian as a subset of the main BCS Web site. Several sections of images were called for, including photos of British firsts, Key People and Workplace Changes. In September the CCS had made progress in assembling relevant images and captions. However, on 4 October the CCS was informed that the BCS did not wish to duplicate the material that already existed for John Kavanagh's book. Furthermore, the BCS "already has timelines in the book, so we can reuse these in some form online without requiring a lot of additional work from everyone. It is suggested that the book could be the centre-piece of the BCS@50 history section online". The services of the CCS are no longer required for a historical Web site.

Reading between the lines, perhaps the original idea of using images from the Our Computer Heritage Pilot Study was inappropriate. The Pilot Study (and its compilers?) is too technical and too limited in scope (1945-1970) to appeal to a wide audience. The Pilot Study is, however, in the nature of 'rescue archaeology' and remains a vital CCS archiving project for which future computer historians may well be thankful. It is a pity that our efforts will have to chug along without much tangible support from other bodies. CCS volunteers are used to this!

Contact Simon Lavington at lavis@essex.ac.uk.

Len Hewitt, Chairman

Pegasus has been running well on most of our fortnightly visits. We managed to obtain a new motor for the Trend paper tape reader and that has been repaired and put back into service. I wish to thank EBM Pabst for the generous donation of the motor. I would also like to thank Rob Fastner (ex Trend) without whose help this paper tape reader would not have been repaired. The Trend paper tape reader and GNT punch, together with a PC, serve as the external tape preparation equipment.

Another major task this year was the replacement of the contacts in the Star/Delta starter. This work was carried out by the museum object maintenance staff and our thanks go to them. The number of visitors to Pegasus has increased since Peter Holland and I met the new Museum Director Martin Earwicker. He came down to meet us and to see Pegasus; we talked and made some suggestions to him. The result is that on Pegasus "in steam" days, there are notices posted and regular Tannoy announcements that the oldest working computer in the world is on display. We normally go home tired but satisfied.

Contact Len Hewitt at leonard.hewitt@ntlworld.com.

Arthur Rowles, Chairman

The Working Party has been meeting regularly to work on the machine, typically four days per month. We do make progress, though much of the time is spent dealing with the routine problems that arise with a machine as old as this one. We regularly experience problems with dirty or corroded relay and connector contacts resulting in that day's 'obligatory setback.' The fact that we do not have a complete set of up-to-date drawings, thanks to the machine having been considerably altered since initial construction, does not help. Powering-up is consistently reliable (almost), and the drum motor usually regulates at the require 4600 rpm (at least in the afternoons!).We are now beginning to trace signals through the more straightforward logic paths.

Contact Arthur Rowles at rowles01@glbalnet.co.uk.

John Harper

Since our report in Resurrection 38 we have now have enough drums to fully populate the front of the machine, as can be seen behind the people in the photo in the picture overleaf. Also all the 'Uncle Walter' plugboards are now wired up and fitted: our previously reported shortages have been overcome thanks to the Otago Peninsular Settlers Museum in Dunedin, New Zealand. We are very grateful to the staff and supporters of the museum who made this possible.

| This shot of the live BBC television interview on 6 September shows from left to right: Jean Valentine (ex WRNS), John Harper, Sarah Campbell (interviewer) and a cameraman. |

Commissioning is making very good progress with over 80% of the subsystems working. However the last sections may not go so well and when we try the whole machine on a real known stop we may find other problems. We are cautiously optimistic but at the same time aware that we are still in new territory. Therefore we are not estimating any timescales to completion.

We can however prove a correct 'stop' on a known menu in static mode. That is, with the menu correctly plugged up, and with all the drums turned by hand to the appropriate position, we have the correct electrical conditions for a 'stop'. This may not appear to be a major achievement but when all the wiring, correct reflector routing and the numerous internal drum connections involved are taken into consideration this is a very major step forward.

When the machine is running this 'stop' condition has to be sensed on high-speed relays. The sense circuits are all in place and tested. The next step is to apply them to the menu and detect a correct 'stop' with the machine running, and then make the information available to the operator. The untested part of this comprises the 'stop and cancel' circuits where the machine continues to rotate until the machine stops in the correct position, and this is then indicated on the outside of the machine. The 'stop and cancel' relays are all in place ready to be tested.

To celebrate the end of construction we wanted to show what we had achieved to the veterans and in particular the WRNS who had operated the Bombes during the war. We did this on the Enigma Weekend of 23-24 September, which was very successful. The team was particularly pleased to see such a large number of veterans, and they went out of their way to congratulate us on what we have achieved.

During the planning for this weekend it was anticipated that there would be interest also from the general public in what had been achieved. The Bletchley Park Trust team therefore arranged a Press Day on 6 September. The response was overwhelming. We spent a whole day giving interviews for television, radio, newspapers and Web-based articles. The amount of resulting publicity exceeded all expectation: we have heard it reached places as far apart as India and the States. We all hope that this publicity will reawaken the general public to what Bletchley Park stands for, so more visitors will come.

The demonstrations put on at the Enigma weekend were not confined to the Bombe. We set out to show an example of all the equipment used at Bletchley Park to decode German Enigma messages. We had on show a three wheel Enigma machine, our Bombe, our Checking Machine (now complete) and a Typex machine that we have modified.

When the settings that were used by the German operator on the Enigma machine have been discovered, all messages recorded by the Y stations have to be decoded. At Bletchley Park they used a modified British Typex machine to act as an Enigma machine. Our team has made the necessary drum inserts and can now decode Enigma messages as was done at the Park during the war

Our Web site is at www.bombe.org.uk/.

| Top | Previous | Next |

Once the computer was established as an effective business tool, someone had to spread the word. The founder of the world's first weekly computer newspaper re- lives the challenges of the early days of IT journalism.

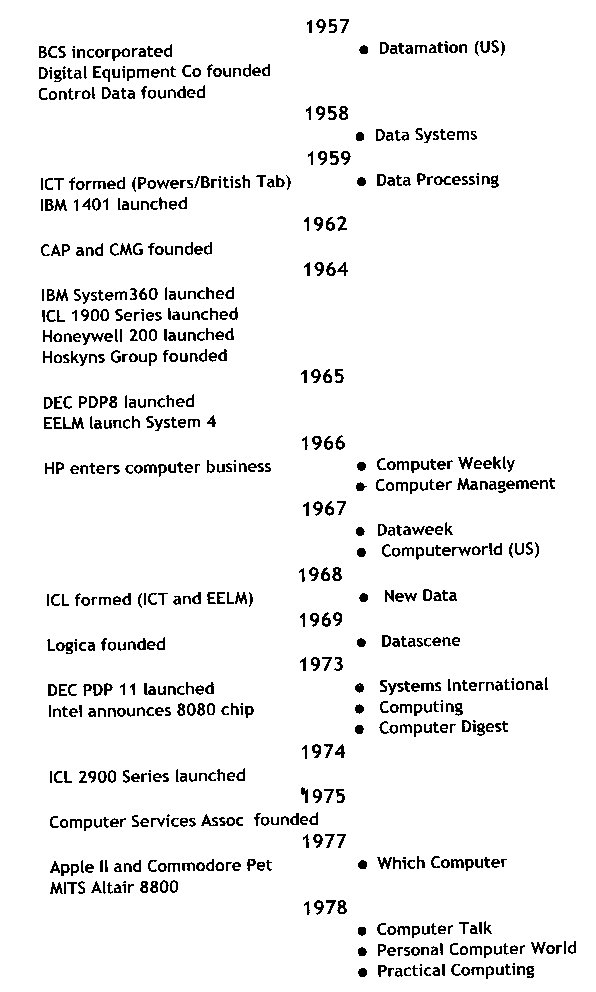

The first notable computer publication was undoubtedly Datamation in the States. It got off to a good start in 1957 and became very widely read, not only in the States but also in this country, and was a substantial publication for many years. It was followed in the UK by Data Systems in 1958 and Data Processing.

Data Systems just beat Data Processing to the draw, but we followed a few months later. I say 'we' because, after two and a half years with ICT, I had come to the conclusion that perhaps I wasn't cut out to live with computers that closely, and I became a journalist on Data Processing.

This was a quarterly magazine for top management and chief executives. The reason for that was that, looking out at this jungle of the computer industry, where 'industry' means both users and manufacturers, about the only people you could identify were the top people, accountants and so on. You had no way of knowing who was working at the coalface.

The magazine was geared to telling people in responsible positions what computers were about. Our early issues did, I think, a reasonable job, covering technical subjects such as electrostatic printing, and descriptions of applications such as ordering and stock control at Rootes Motors; and there was one that purported to tell the whole story of IBM computers in just a few pages (it was a shorter story in those days). I remember an article on Orion, which I followed up a few years later by writing one on the Orion Monitor Program. I enjoyed doing that one very much, because I knew very little about software at that time.

Figure 1: Timeline 1957-78 (IT industry events left, publication launches right)

After the launch of Data Processing in 1959, there was a long period when very little happened on the publishing side. In the wide world outside, though, a lot happened. The year 1959 saw the merger of British Tabulating Machine Co and Powers Samas to form ICT and the launch of the IBM 1401, a key early machine. A few years later the first software houses, were founded, with CAP being formed by Alex d'Agapayeff and Barney Gibbens, and CMG by Doug Gorman.

Then we had that most significant of all new events, the launch of the IBM 360 in 1964, which brought a great deal of order to what had been a fairly chaotic situation. It was the first range of compatible computers, and that set the scene for the whole of the rest of that mainframe period. ICL followed up very quickly with the 1900 Series, based on the original Ferranti Packard machine. The Honeywell 200 was launched: I mention that one because it gave the early 360s quite a run for their money, as it had a compatibility program.

Then John Hoskyns - now Sir John - founded the Hoskyns Group. In 1965 we had the launch of both the System 4 by English Electric and the PDP-8 by Digital Equipment Company.

Now all those things happening were of great frustration to me (by that time I was editor of Data Processing). All this lovely news was breaking. Data Processing was by then a bi-monthly, so we produced just six issues a year, and it was quite impossible to carry all that news, which was in any case dead by the time we published. So in 1965 I came up with a proposal for a new publication.

I had thought initially of a newsletter with a low cover price, but in the course of looking at it we decided that it should be a controlled circulation publication, free to the user or reader, and that the main source of revenue would be job advertising.

That was an important decision, because it was a relatively untapped source. When I first joined ICT, I was always amazed by the quiet that reigned over the office on a Monday morning while everybody flicked through the appointments pages of the Daily Telegraph. That memory stayed with me, and in 1966 I thought that there's some money out there and we're not getting a share of it.

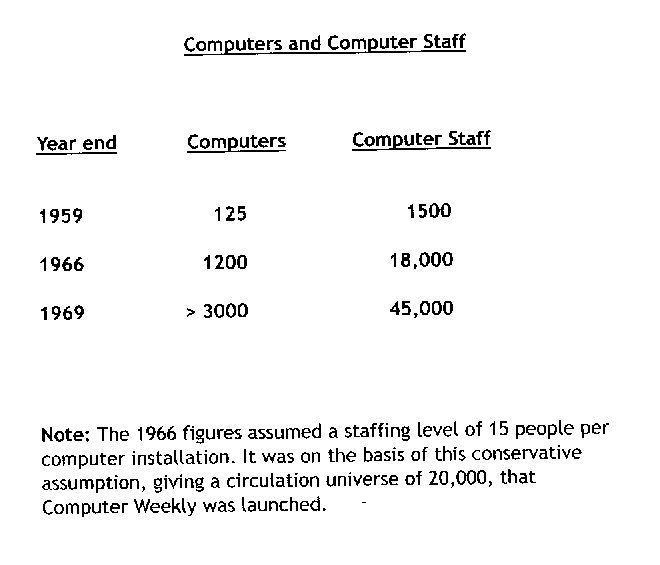

It was not at all clear when we launched Computer Weekly just exactly what we were launching into. We had our ideas, or else we'd never have launched it, but the outlook was by no means clear. In 1959 there were not more than about 125 computers in the country, employing about 1500 computer staff. By 1966, when we were thinking of the launch, there had been some appreciable movement: there were about 1200 computers and 18,000 staff. They were the people we had to reach.

We started off on the assumption that there was about 15 computer staff per installation (I think that was broadly right, if you even it out from very small to very large installations). Those 18,000 people were

Figure 2: Computer staff universe at launch of Computer Weekly

accounted for by the DP Manager, chief programmer, systems analysts, programmers and computer operators. That was the basic computer universe that we going to. We bumped it up to about 20,000 by including chief accountants and company secretaries.

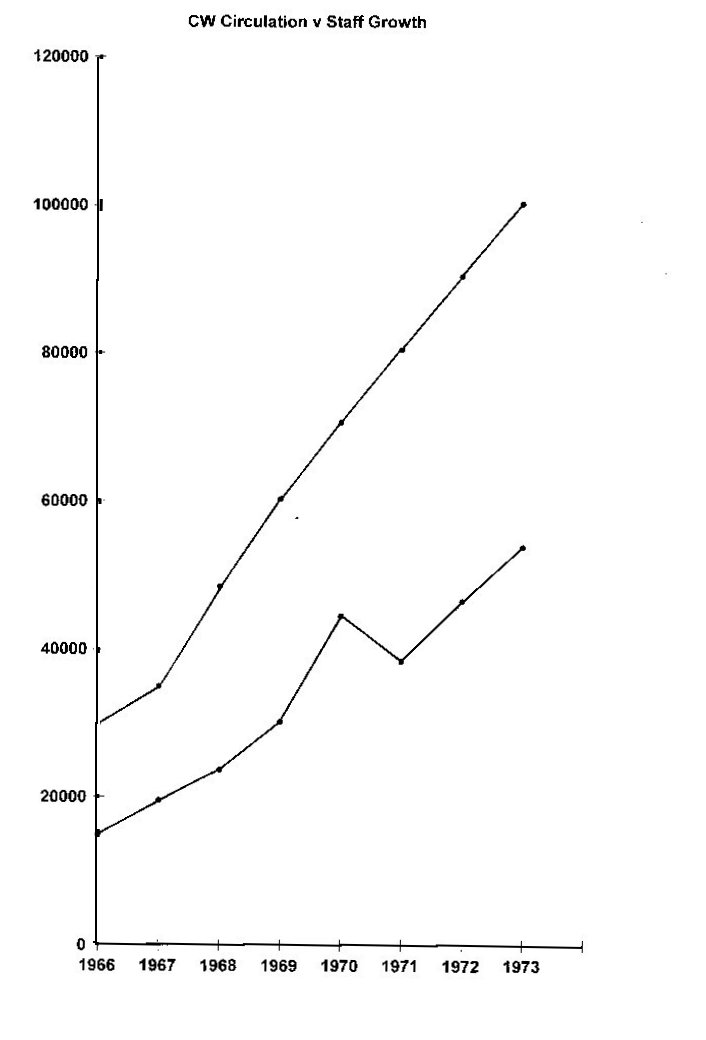

We first published Computer Weekly in September 1966. We were looking for 5000 requested readers, but we had 7500 with the first issue, and we went on to reach a figure of 15,000 in the first year.

The first issue of Computer Weekly was hailed as a great success, and seemed to be one judging by the response. It contained a range of different items. A multi-access system for Harwell was the main story; there was a 1967 target for IBM's official Algol compiler; and there was a guest opinion by Basil de Ferranti. The first lead article, entitled 'Ten Years of Growth', was about the BCS and was written by John Mackarness, secretary of the BCS.

So we were off to what I think was a good start. Of course the unique position that we had, by being first, couldn't last. Dataweek followed in 1967, just about a year later, and at the same time ComputerWorld was launched in the States. In the days when I occasionally met Pat McGovern, the publisher, he would always say "We're the biggest newspaper in the world", and I would say "Yes, but we were first".

Then came a couple of smaller publications, New Data and Data Scene. They were me-too publications, trying to replicate what Computer Weekly was doing.

In 1972 Charles Ross came to me, wearing his BCS hat, and said they were thinking of trying to get into the publishing market, and would I like to put up a proposal. I scratched my head for a while and thought about what to do; it was probably not going to be possible to convert Computer Weekly into a BCS journal for them. I did put up a proposal, but it obviously didn't meet with his favour, because a deal was done with Haymarket which introduced Computing, giving us a real run for our money.

The first issue of Computing had the main story 'ICL to set up Italian office'; I'm not sure how effective that was. Tom Hudson, then chairman of ICL, was pictured on the front page. There was a story about CAP losing Tony Hardcastle. It was obviously a very professional job, well put together, and as I say it did give us a run for our money. By August 1975 Computing had acquired both Dataweek and Computer Digest, which narrowed the publishing field quite a bit.

There was always space for new publications, because of the economics of controlled circulation publishing. As the number of computer staff increases, there is a widening gap between the total computing population and the number any one publication can reach.

That widening gap occurs because with a controlled circulation paper your costs are fixed, and you cannot go on increasing your ad rates to allow you to print more and more copies. You have to limit the number of copies you produce. Nonetheless Computer Weekly was a considerable success, and I'm pleased that it was.

Other things were happening in the computer world. One of the key developments was that a whole parallel world of computing, with dedicated systems for specific applications, commercial and scientific, had grown up since the PDP-8 was launched in 1965. That was an important world, because many of the jobs that were being done were commercial, and could have been done by general purpose computers. This was amplified in 1973 with the launch of the PDP-11, which was an amazing success for the next 20 years or so; it was the nineties before it was phased out.

Figure 3: Computer Weekly circulation (bottom) compared to computer staff growth (top)

All this gave scope for the launch of Systems International. A chap called Bill Gledhill launched it with the backing of a very interesting entrepreneur, a man called Peter Michael (now Sir Peter), who had founded a software company, Cray Electronics, which subsequently changed its name to the Anite Group. He had also been the driving force behind Quantel, whose Paintbox graphic arts software was used to provide digitised special effects for TV and film production.

A few years after its launch, in 1978, we acquired Systems International. When I say 'we' I mean my employers who by this time were IPC. It was a successful addition to the stable.

Meanwhile, Which Computer? was I think the last of the general-purpose publications, by which I mean publications dealing with the whole range of commercial computing systems. There was so much kit on the market by that stage that a comparative journal, one that would look at a number of like systems, was a good idea, and it succeeded.

Now we come to what I think is the cut-off point in our story. In 1973 Intel announced the 8080, a very usable chip that underlay many different systems. By 1977 this line of development had spawned those two hobbyist and home computer systems, the Apple 2 and Commodore Pet, which were used not only in the home but in many other contexts as well. At around the same time we got the Altair 8800, which I mention because without it we might not have had Bill Gates. He produced the first DOS compiler for the Altair.

That led to the arrival of Personal Computer World and Practical Computing, which takes us into a whole new world of publishing, when the handful of established publications suddenly multiplied tenfold. There are today hundreds and hundreds of papers relating to specific home computers and catering for the needs of the computer shopper. Today the computer publishing world is altogether different.

I think that what we brought in those first 20 years with our initial publications was something very important. We tried to bring to the computer fraternity news about what was going on: for example news of new technology; interpretation of what new developments meant; and interpretation in terms of editorial analysis of issues that were outstanding at the time.

We took a strong position, for example, on databanks. In 1970 we supported something called the Databank Workshop, a high level two-day conference, which looked at the impact of computers on society. Since then, of course, everybody's reliance on the credit card has ruined the idea that individuals could enjoy any privacy, and in any case we have CCTVs on every corner and all the rest of it. We now live in a very highly monitored society.

We were also very interested in education. In 1974 or 1975 we put on a competition for secondary schools, sponsored by ourselves and Digital Equipment Company, and we gave away a Classic 8500 computer after a well-fought competition that lasted for several months There was a rigorous weeding-out, and then four or five top schools came to London to make presentations, and the winner was presented with the computer by Patrick Moore, taking time off from looking through his telescope.

We hope that we gave something to the industry, not least in terms of looking at professionalism, for example in our relationship with the British Computer Society (a BCS page has run from then until now in Computer Weekly). We hope also that we stimulated people through our editorial about what was going on in the computer world. And at times perhaps we've entertained people as well.

Editor's note: This is an edited transcript of the talk given by the author to the Society at the Building the Profession seminar at the Science Museum on 24 March 2005. The Editor acknowledges with gratitude the work of Hamish Carmichael in creating the transcript. Chris Hipwell can be contacted at chriship37@yahoo.co.uk.

Editorial contact detailsReaders wishing to contact the Editor may do so by email to wk@nenticknap.fsnet.co.uk. |

| Top | Previous | Next |

Most articles in Resurrection have dealt with events of the second half of the 20th century. The computer was, though, born into a world that had been using sophisticated aids to arithmetic for at least 500 years. The author describes the development and use of pre-computing computational aids.

After studying a large number of computational objects from the fourteenth to the twentieth century it becomes apparent that most of them fell into two broad categories: those objects designed by people who were understanding and advocating arithmetic, and those objects designed by people aiding and abetting avoidance of arithmetic.

It is interesting to look at the extent to which the polarisation occurred, what categorises the combatants, the time when the debate was most pronounced, and possible patterns of supremacy of one attitude over the other. Quite often the instruments themselves are the subject of controversy.

During the fifteenth century a sea-change was taking place in Europe. Commerce was rapidly becoming more complex, and the practice of venture accounting - treating each voyage as a separate enterprise - was replaced by a continuous accounting system.

It started in Italy, where mercantile capitalism was particularly vigorous. Pen reckoning then began to spread throughout Europe. From as early as the fourteenth century, merchants from the north travelled to Italy in order to learn the arts of double entry accounting, commercial arithmetic and pen reckoning, from a reckoning master (not from a university where Latin was still the predominant study). One father advised his son to "rise early, go to church regularly, and pay attention to your arithmetic teacher".

During the fifteenth century the momentum increased, so it's fair to say that by about 1500 what we would call ordinary arithmetic was the concern of a large number of people.

An anecdote from Tobias Danzig's work suggests that students had to go to Italy in order to learn multiplication and division; Germany was all right only for addition and subtraction. This does suggest that problems of multiplication and division on the abacus were a factor in the demise of the latter, because in fact Germany was the last area to continue using the abacus within Europe (there's a big question about why the abacus survived so long in the East, which is beyond the scope of this presentation).

It appears that the abacus or a counting cloth or board, which are all essentially the same thing, together with a system of tallies could cope with a series of records in a relatively static society, but was less suited to constantly changing complex accounts which dealt with widespread customers. The Exchequers which used the cloths tended to be centralised; people in general had their results in the form of tallies but did not perform calculations themselves. Some of the earliest instruments we have are a set of tallies dating to about 1440.

At this time the abacus clearly has to be seen as an instrument of avoidance. However, although there was recognised pain in learning arithmetic by pen reckoning, the vast majority of the arithmetic manuals which appeared across Europe following the introduction of printing also promoted avoidance wherever possible.

One of the first books published on a related subject in English, in 1537, principally consisted of a ready reckoner in various quantities. Measuring systems were very complicated before the introduction of the imperial system in the early nineteenth century. Ready reckoners in all their forms can be classed as instruments of avoidance, and many of them you can see in the Science Museum. Very often mathematical instruments of all sorts of types, right up until the nineteenth century, have multiplication tables or other forms of ready reckoner on them.

Interestingly the books remembered in the study of the history of mathematics tend to be those which see arithmetic as something beyond the merely useful, as something to be understood and enjoyed rather than to be made easy. Often these works are seen as intrinsically 'better' than those which do not elevate the subject into anything other than a tool.

It's now difficult to detect which books were most acceptable in their own time for teaching the basics other than by which were reprinted. Though here we have to be careful, because simply buying a book is no guarantee that it was read and understood, as we know today from the work of Stephen Hawking - A Brief History of Time is a notoriously well-bought but not read or understood book.

This quote from Noel Bridges in 1660 is very similar: "I have often observed that many who have turned over several tracts of arithmetic in the pretence of taking pains to attain the art run from the material part thereof, and humour their fancy by squandering time in asking trivial questions and taking up eggs and stones."

The first book of arithmetic written in English was Robert Recorde's The Grounde of Artes in 1543. Recorde introduced the equals sign and used the Copernican system in a subsequent book on astronomy, which was new territory at the time. He is widely regarded as the founder of English arithmetic.

He confirmed the backward state of mathematics in England, but stressed that he was concerned about more than just utility. "Number is the ground of all Man's affairs, so that without it no tale can be told. No communication without it can be long continued. No marketing without it can duly be ended, nor can any business that men have be completed. These commodities, if there were none other, were sufficient to prove the worthiness of Number."

He also said, and I'm afraid this is where the presentation breaks into verse,

"There are other innumerable, far passing all these,

Which declare Number to exceed all praise;

Wherefore in all great works by clerks so much desired

Or auditors so richly feared

What causes geometricians so highly advanced?

Or why are astronomers so greatly advanced?

Because that by Number such things they should find

Which else should far excel man's mind."

Clearly there was value in the understanding of arithmetic and the broadening of the mind that its study produced. He even suggested that his readers should practise finger-counting because it was an interesting thing to do!

The pain of learning to do arithmetic by pen reckoning is well summed-up in this nice little rhyme which is well-known, or at least was until the early twentieth century :

"Multiplication is my vexation

Division is quite as bad;

The golden rule is my stumbling-stool,

And practice drives me mad."

The seventeenth century produced a wealth of avoiding devices for those with little aptitude for arithmetic. One of the earliest was Napier's bones. Napier's better-known invention - logarithms - doubled the lives of astronomers, according to Laplace, so we should not belittle avoidance.

Napier in a dedicatory epistle to the Earl of Dunfermline in his "Rhabdology" (calculation with rods) in 1617 wrote: "Before calculation was a difficult and lengthy process, the tedium of which deters many from the study of mathematics. I have always tried with such strength and talent as I possess to expedite the process. The use of the system of bones avoids multiplication and substitutes addition." And one of the little verses scattered around the start of the book goes:

"The tasks that fill beginners with dismay

This little book has banished clear away."

There's nothing about the love of arithmetic here.

The Jewel was another device, promoted in the same year by Joseph Harper, who claimed it "had the ability to effect the same as the pen with less time and more facility." It was complicated, and was not a success.

A well-known conflict in the history of mathematics is that between William Oughtred and Richard Delamain over the invention of the slide rule in 1632. The debate spread to the use of instruments in general.

Oughtred accused Delamain of making his students "only doers of tricks" by teaching them the use of instruments without any theoretical grounding. Oughtred said: "The true way of art is not by instruments but by demonstration, and the use of instruments is indeed excellent if a man be an artist but contemptible if a man be opposed to art". Similarly Bishop Ward, on being shown a Gunter sector, is said to have exclaimed: "This is a mere showing of tricks, man".

Delamain argued that restricting the use of instruments to those who understood the underlying theory was too strict and would drive students from mathematics. Hill said that this showed a breakdown in the unity of mathematical practice in England, but this presentation argues that the underlying tension had been there all the time and besets the entire history of elementary mathematics.

By the second half of the seventeenth century it doesn't seem to be so necessary to stress the utility of arithmetic in such a down to earth manner. This is an excerpt from Noah Bridges in 1653:

"Oh ye sacred numbers, to whose chiefest art

Poets and prophets do their wreaths impart,

Why are wise few, fools numerous in their excess

For, wanting number, they are numberless".

Then there are the famous entries in Samuel Pepys's diary. 9th July 1662: "Up by 4 o'clock, and at my multiplication hard". 11th July: "Up by 4 o'clock and hard at my multiplication table, which I have now almost mastered". Pepys was a learned man who later became a member of the Royal Society, so that's quite a surprise.

David Bryden has written on Charles Cotterell's instrument which was proposed in 1667 to help those who could neither read nor write in arithmetic. The intelligentsia was not impressed. Robert Hobbes wrote a book about arithmetical instruments in 1673 and condemned them in general: "The best way for addition and subtraction is by setting down the numbers on paper when they can be quickly added or subtracted. For those kinds of operations in arithmetic an instrument is wholly insignificant, and at best will come short of common counters."

Edward Cocker wrote the well-known Tutor to Writing and Arithmetic in 1664, which was reprinted throughout the eighteenth century. Historians of mathematics have always denigrated Cocker. Susan Cunningham in 1904, with an attitude typical of her time, said: "Shillings multiply shillings without demur, or products are formed of acres and pounds. Any concrete quantity becomes abstract at a touch."

These crimes are hard to find, and indeed Cocker is incredibly encouraging. "Be not discouraged, but begin confidently and proceed industriously. He can add that knows 1 and 1 make 2."

Augustus de Morgan spent five pages condemning Cocker in 1835. "I am of the opinion that a very great deterioration in the work of elementary arithmetic is to be traced to the time that the book called after Cocker began to prevail."

So, summing up, many books have been written and instruments made which emphasise the avoidance side of the argument. Only a few lonely voices such as Oughtred and Recorde suggest that mathematics can broaden the mind.

Hill points out that Oughtred did not have to make a living from his mathematical enterprises, and there's certainly a class issue not difficult to detect - the size of the book relates to how much use and avoidance are stressed. For example, William Labour, in a large and expensive volume called Cursus Mathematicus of 1690, said "None afford a better mind for repentance than mathematical do. Therefore in a dull solitude or vacancy of business, both of which may happen to scholars or to gentlemen, these are amiable company which yield a delightful and innocent expense for vacant hours." This is quite the opposite intention of the avoidance faction.

Geoffrey Howson rightly states that in the absence of any Church or state coordinated system the provision of mathematical education often came to depend on private enterprise. "Frequently, in order to attract financial support, this led to an emphasis on utilitarian ends". Certainly that was the situation during the eighteenth century.

Other things started to happen in the early nineteenth century. About 1817 arithmetic discovered the Enlightenment. One of the first writers to break out of the mould of the elementary arithmetic, while still teaching it, was John Leslie. A new genre became apparent with a psychological viewpoint, reliant on Locke's concept of the senses, a comparison of humans and animals not seen since Recorde, and a survey of different cultures, both historical and geographical.

The Encyclopaedia Metropolitana articles for this period, by Ian Peacock in particular, are completely different from the earlier resumés of arithmetic, and they go into every possible facet.

There was a distinct movement in elementary education springing up. Samuel Wilderspin published a number of works, such as a discussion of the abacus as an educational aid, turning the abacus round from avoiding to educating. Pestalozzi was beginning to attract a very small following in parts of continental Europe. A report in 1841 of a school in Battersea states: "The use of the Pestalozzi method dispels the gloom that must attend the most expert use of the common rules of arithmetic which commonly afford the pupil little light to guide his steps off the beaten path illuminated by the rules."

Froebel was another who stressed the concrete aims and their need to be examined. We're fortunate to have in the Science Museum collection an arithmetic aid by Sonnenschein, a pioneering writer and teacher of the mid nineteenth century.

All these writers advocate the understanding of arithmetic, and the use of instruments to facilitate that understanding. However the average child - or adult - learning arithmetic in the nineteenth century was not likely to be aware of these reforms. It was not until the twentieth century that they actually benefited the majority of children. Maria Montessori advocated a similar approach. Concrete learning aids were still seen as pioneering in 1900.

Can it be said that periods of wealth and stability tend to favour avoidance and periods of nervousness advocacy? There does appear to be this connection. Recorde worried about England's position, while De Morgan was afraid that we were failing to keep up in mathematics with the Continent. Doing what people can understand when just manipulating is not sufficient.

Apart from the overtly educational blocks and number balances of the advocacy pioneers, instruments are usually promoted as avoiding mechanisms and shunned by the mathematical elite. But strangely they have often been re-introduced at a later stage as an aid to understanding. This happened with Napier's bones in the late nineteenth century, the abacus and mechanical calculators in the twentieth century, and now by many teachers who have incorporated the electronic calculator as a tool of learning.

Editor's note: This is an edited transcript of the talk given by the author to the Society at the Computing Before Computers seminar at the Science Museum on 12 May 2005. The Editor acknowledges with gratitude the work of Hamish Carmichael in creating the transcript. Dr Wess can be contacted at jane.wess@nmsi.ac.uk.

| Top | Previous | Next |

The Society has its own Web site, located at www.bcs.org.uk/sg/ccs. It contains electronic copies of all past issues of Resurrection, in both HTML and PDF formats, which can be downloaded for printing. We also have an FTP site at ftp.cs.man.ac.uk/pub/CCS-Archive, where there is other material for downloading including simulators for historic machines. Please note that this latter URL is case-sensitive.

| Top | Previous | Next |

The word 'computer' originally meant a person, and only came to indicate a machine in the late 1950s. The author describes the extensive use of human computers in the production of astronomical tables over 200 years ago.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, a computer is "one who computes, a calculator, a reckoner, specifically a person employed to make calculations in an observatory, in surveying, etc etc". That definition dates from the mid- seventeenth century, and specifically to Thomas Brown, a doctor in Norwich.

Today I'd like to talk about just one example about how computers, in this human sense, were used to do large scientific calculations in the eighteenth century. England was then very much a maritime nation. Overseas trade was crucial to the nation's prosperity. The ability to wage war and to control colonial interests was paramount. It was therefore essential that British ships could navigate in both a safe and timely manner around the world.

Many readers will be familiar with the story of the Longitude Prize. In 1714 the British Government offered £20,000 (equivalent today to about two million pounds) to whoever could provide a practical solution to the problem of finding longitude at sea. Essentially the difference in longitude between two places on the earth's surface is the same as the difference in time between those places.

Eventually in 1773 John Harrison won the Longitude Prize for his watch - H4 - which could be taken to sea to maintain Greenwich Time. It could therefore be used to compare Greenwich Time with a ship's local time as obtained by taking observations of the sun's altitude, the difference between the times being the difference in longitude between Greenwich and where the ship happened to be.

But although Harrison won the prize, for the vast majority of navigators it was not really a practical solution. It cost about £200, well out of the reach of most navigators of the time. Only high profile explorers such as James Cook or the ships being run by the East India Company could afford to carry the watch. For anyone else, an alternative solution was provided by the Astronomer Royal of the time, Nevil Maskelyne.

Maskelyne was appointed Astronomer Royal in 1765. For the previous 10 years he had been working on the method of using lunar distances to calculate longitude. The system was well understood in principle and was based on the fact that the distance between the moon and any one of the fixed stars changed over time, but at any given instant that distance was the same regardless of where on the surface of the earth it was observed. Therefore when a lunar distance was observed from the deck of a ship halfway to Jamaica, say, the difference between local time and the time at Greenwich when that same lunar distance was predicted was the difference between the ship's longitude and Greenwich.

The difficulty was that the calculations to work out the predicted lunar distance at Greenwich took over four hours to perform. Not only would the ship have moved significantly in those four hours if it had a fair wind, but also few eighteenth century sailors would have chosen to spend four hours on a calculation even if they had the skill to do so. Maskelyne's innovation was to provide pre-computed lunar distances and other astronomical tables in his annual Nautical Almanac, which was first published in 1767.

The use of the pre-computed lunar distances in the Nautical Almanac reduced the calculation time to 30 minutes - still quite tedious, but a great improvement on four hours. The Nautical Almanac sold for six shillings annually, and that was also a big improvement on the £200 for a Harrison's watch.

In order to be able to publish the Nautical Almanac on an annual basis Maskelyne had a find a way to do all the necessary calculations in a timely manner. Each Nautical Almanac contained tables of the positions of the Moon, Planets and fixed stars, the lunar distances for every three hours of every day of every month of the year, and several other astronomical tables.

The preparation of the complete Nautical Almanac was a huge undertaking, for the calculation of any one term in the Almanac could involve the looking up of up to 12 entries in mathematical or astronomical tables and performing up to 14 arithmetical operations on those figures, most of which used eight-figure sets of sexagesimals. This had to be done for every day of every month of every year. It was very repetitive, very tedious work. It also had to be accurate. In the worst case scenario, a single error in one digit in the Nautical Almanac could result in a navigational error of 60 miles, which could have fatal consequences if a ship was approaching land in poor visibility.

Maskelyne's solution to the problem was to employ a network of human computers, located throughout England, to compute the Nautical Almanac on a piecework basis, working in their own homes.

The computers were widely spread, from the north-east of England right down to Cornwall and Devon, and from Shropshire in the west right the way over to Norwich in the east, plus lots of places in between. Because he kept accurate records of the work that was being done we know all the names of the computers that Maskelyne employed and how long they worked for him. At any one time there could be as few as four people working on the Nautical Almanac or as many as nine.

Maskelyne was very prescriptive in how the work was carried out. He had two computers calculate each month of the Nautical Almanac. Their results were sent back to Maskelyne who then sent them on to a comparer to check them for accuracy and to compare the work between the two computers.

The computers had to do the work in a prescribed way. When a new computer was appointed they were sent a series of books and tables with which to work and a set of algorithms, or as Maskelyne called them 'computing rules', for each calculation.

Maskelyne was very strict in insisting that they were followed. From time to time he amended his computing rules and wrote personally to each computer outlining the new instructions. He often demonstrated his principles in the letters.

The list of books that he sent out to each of his computers was quite extensive, and they were expected to account for them all, so that when one computer resigned they could be assigned to another. For example in March 1800 one of his computers, Philip Turner, died suddenly owing rent to his landlord, and in the end Maskelyne had to pay £10 for the safe return of his books from the pawnshop.

As I've said, in any one month Maskelyne would assign two computers to do all the work associated with that month. When they had completed their calculations they sent their handwritten tables back to Maskelyne in Greenwich. Some computers would finish their work in three to four weeks, others took three to four months. Maskelyne then passed the tables on to a third person, the comparer, who checked and compared the work of the two computers. The comparer also independently calculated some typical values as an additional check against systematic errors. Where discrepancies were found between the computers, the comparer wrote back to the computers with corrections.

One calculation was the Moon's longitude and latitude. One computer was asked to calculate this for noon of each day, and the other computer, or as he was called the 'anti-computer', was asked to calculate it for midnight of each day. When the comparer received the two sets of tables he merged them and then took six differences to check for any errors. Only when he was sure that they were correct did he send the tables back to the computers for them to interpolate the Moon's position for every three hours and then to calculate the all-important lunar differences.

As you can imagine there was a great deal of communication between Maskelyne and his comparers and the computers. Several months were often being calculated in parallel by different computers, but all was managed smoothly and efficiently by Maskelyne and his comparers. Practically all the communication was done by post. In the 1770s a letter between London and Cambridge took three days, but by 1784 the new mail coach postal service had been introduced on the new turnpike road and the speed of delivery improved to 24 hours.

While we know that repeating a calculation and then comparing the results is not the most efficient or effective way to find errors. Maskelyne's method certainly worked well in practice, and during his lifetime the Nautical Almanac had an enviable reputation for accuracy. This was due to the care which Maskelyne exercised in both training the computers and getting them to build in checks on their own work before it got sent to the comparer. From letters between computers we know that differencing was used by computers as well as by the comparer.

Most computers appear to have taken their work seriously and kept to Maskelyne's rigid rules and procedures. Indeed the system was set up to ensure that they did. I'll give you an example: in 1770 a comparer, one Malachy Hitchens, discovered that two computers, Joseph Keach and Reuben Robbins, had been copying each other's work instead of working independently. The tables that they submitted were much too similar to be true. Maskelyne promptly fired them both, and demanded extra payment for the extra work they had caused the comparer.

Keach and Robbins both lived in London, were members of the same social circle and went to the same coffee house. Following that experience, Maskelyne tried in future to ensure that the computers assigned to one Nautical Almanac month lived geographically distant from one another, which explains why he had them dotted all over the country.

As an additional check, Maskelyne annually compared the tables of the Nautical Almanac against the French Connaissance des Temps, which had similar, but not exactly the same, tables, and where necessary he published Errata. However, usually the list of Errata in the Connaissance des Temps was longer than that for the Nautical Almanac.

Because of Maskelyne's scrupulous record-keeping, we know pretty accurately who computed which month of the Nautical Almanac for the years 1767 to 1811. Over that period Maskelyne employed 35 computers.

Computing for the Nautical Almanac was rarely a full-time job. Most computers fitted in the work around other employment. Some were Church of England vicars; for example Malachy Hitchens was a vicar in Cornwall. A lot of the others were schoolmasters; for example William Wales travelled with Captain Cook and then became mathematical master at Christ's Hospital School in Greenwich, but worked for Maskelyne, on and off, for several years, and also introduced his brother, John Wales, who lived in Wakefield in Yorkshire, to the work.

William Wales was a schoolmaster at quite a prestigious school. Henry Andrews, on the other hand, was a schoolmaster at Royston in Hertfordshire, and ran a very small local school; he and his wife took in some boarders. He also ran a bookshop, sold mathematical instruments, and did the calculations for Moore's Almanac.

Others were surveyors. Others still had worked for Maskelyne as observing assistants at Greenwich, or were astronomers on the voyages of Cook and Vancouver, and wanted extra income while they were in port. An example is John Crossley, who travelled with Vancouver, and later became President of the Spitalfields Mathematical Society.

For two, though, computing was a full-time job. Joshua Moore was a young man living in the Angel Inn in Cambridge who worked full-time on the Nautical Almanac before emigrating to America in 1793. We don't know how he made his living in America, but the Jefferson Papers in the Library of Congress contain letters from him to Jefferson advising on how to find longitude during the mapping of the American interior.

The other full-time computer was Mary Edwards. She worked on the Nautical Almanac for over 40 years, and was the only woman employed by Maskelyne. She lived in Ludlow, in a house that is still standing today.

Initially her husband John had been officially employed to do the calculations. John was a clergyman, who had a strong interest in developing mirrors for reflecting telescopes. He died in 1784 having accidentally poisoned himself by inhaling arsenic fumes while making metal alloys, and he left Mary homeless and in debt with two young children to bring up.

However, it turned out that she had been doing the Nautical Almanac calculations all along, so Maskelyne just continued to supply her with work, and continued to pay her; there is no break in the account books at all. The name Mary is simply substituted for John. She worked on the Nautical Almanac for over 40 years, supporting herself and her two daughters, and earned a pension from the Board of Longitude.

I hope I've given you an insight into how computers were used in the scientific context, and in a context where the work wasn't broken down into individual mechanistic parts. There weren't specialisms; there wasn't one computer for each part of the calculation. Each computer did the whole calculation. But it was brought together by the administration of Maskelyne in Greenwich.

Editor's note: This is an edited transcript of the talk given by the author to the Society at the Computing Before Computers seminar at the Science Museum on 12 May 2005. The Editor acknowledges with gratitude the work of Hamish Carmichael in creating the transcript. Dr Croarken can be contacted at mary@croarken.freeserve.co.uk.

North West Group contact detailsChairman Tom Hinchliffe: Tel: 01663 765040. |

| Top | Previous | Next |

Every Tuesday at 1200 and 1400 Demonstrations of the replica Small-Scale Experimental Machine at Manchester Museum of Science and Industry.

Daily except bank holidays Guided tours and exhibitions at Bletchley Park, price £10.00, or £8.00 for children and concessions (prices are raised on some weekends when there are additional attractions). Exhibition of wartime code-breaking equipment and procedures, including the replica Colossus, plus 60 minute tours of the wartime buildings. Go to www.bletchleypark.org.uk to check details of times and special events.

16 January 2007 NWG seminar on "System 4 to New Range Architecture". Speaker Peter Wharton.

25 January 2007 Joint event with BCS Fortran Specialist Group on Fifty Years of Fortran (at BCS Headquarters, Davidson Building, Southampton Street, London) (readers wishing to attend should contact Peter Crouch at pccrouch@bcs.org.uk).

15 February 2007 London seminar on Elliott Digital Computers 1947-67. Speaker Professor Simon Lavington.

20 February 2007 NWG seminar on Elliott Digital Computers 1947-67. Speaker Professor Simon Lavington.

20 March 2007 NWG seminar on Unseen Museum Artefacts. Speaker Jenny Wetton.

12-14 July 2007 BCS 50th anniversary conference at Bletchley Park (12 July) and BCS offices in Southampton Street, London (13-14 July).

Details are subject to change. Members wishing to attend any meeting are advised to check the Society Web site or in the Events Diary columns of Computing and Computer Weekly, where accurate final details will be published nearer the time. London meetings take place in the Director's Suite of the Science Museum, starting at 1430. North West Group meetings take place in the Conference room at the Manchester Museum of Science and Industry, starting at 1730; tea is served from 1700.

Queries about London meetings should be addressed to David Anderson at cdpa@btinternet.com, and about Manchester meetings to William Gunn at william.gunn@ntlworld.com.

| Top | Previous | Next |

[The printed version carries contact details of committee members]

Chairman Dr Roger Johnson FBCS

Vice-Chairman Tony Sale Hon FBCS

Secretary and Chairman, DEC Working Party Kevin Murrell

Email: kevin@ps8.co.uk

Treasurer Dan Hayton

Science Museum representative Tilly Blyth

National Archives representative David Glover

Computer Museum at Bletchley Park representative Pete Chilvers

Chairman, Elliott 803 Working Party John Sinclair

Chairman, Elliott 401 Working Party Arthur Rowles

Chairman, Pegasus Working Party Len Hewitt MBCS

Chairman, Bombe Rebuild Project John Harper CEng, MIEE, MBCS

Chairman, Software Conservation Dr Dave Holdsworth CEng Hon FBCS

Digital Archivist & Chairman, Our Computer Heritage Working Party Professor Simon Lavington FBCS FIEE CEng

Editor, Resurrection Nicholas Enticknap

Archivist Hamish Carmichael FBCS

Meetings Secretary and Web Site Editor Dr David Anderson

Chairman, North West Group Tom Hinchliffe

Peter Barnes FBCS

Chris Burton Ceng FIEE FBCS

Dr Martin Campbell-Kelly

George Davis CEng Hon FBCS

Peter Holland

Eric Jukes

Ernest Morris FBCS

Dr Doron Swade CEng FBCS

Readers who have general queries to put to the Society should address them to the Secretary: contact details are given elsewhere.

Members who move house should notify Kevin Murrell of their new address to ensure that they continue to receive copies of Resurrection. Those who are also members of the BCS should note that the CCS membership is different from the BCS list and so needs to be maintained separately.

| Top | Previous |

The Computer Conservation Society (CCS) is a co-operative venture between the British Computer Society, the Science Museum of London and the Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester.

The CCS was constituted in September 1989 as a Specialist Group of the British Computer Society (BCS). It thus is covered by the Royal Charter and charitable status of the BCS.

The aims of the CCS are to

Membership is open to anyone interested in computer conservation and the history of computing.

The CCS is funded and supported by voluntary subscriptions from members, a grant from the BCS, fees from corporate membership, donations, and by the free use of Science Museum facilities. Some charges may be made for publications and attendance at seminars and conferences.

There are a number of active Working Parties on specific computer restorations and early computer technologies and software. Younger people are especially encouraged to take part in order to achieve skills transfer.

| ||||||||||